S&S Wakayama Special Loopwheel Products.

Whenever we decide to release our own product, we always have the conversation about whether we should. This is always a long, deep conversation that dives deep into what our vendors are already making, what's missing from our wardrobes, and what we want to see go out into the world with our name stamped on it. We can make nearly anything we could want, but if there's no reason to do so, we won't.

We wanted a loopwheel tee that was just right for us, something that didn't already exist in our deep line up of loopwheel knits from The Real McCoy's and Merz B. Schwanen. The result is a t-shirt that augments and extends our selection, with a fit coming from months and months of sampling and tweaking, utilizing every bit of experience and opinion from our entire team to get it just right.

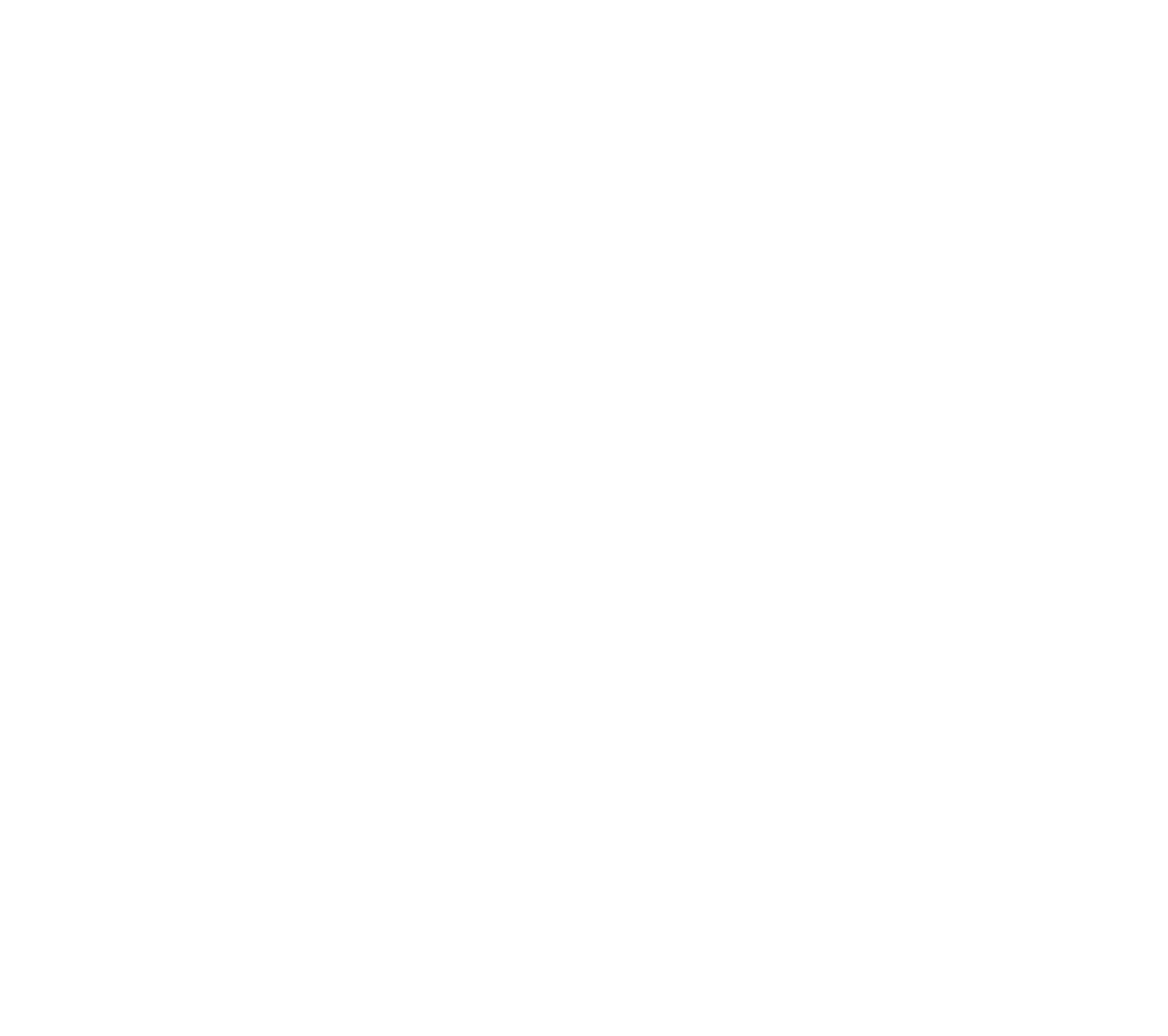

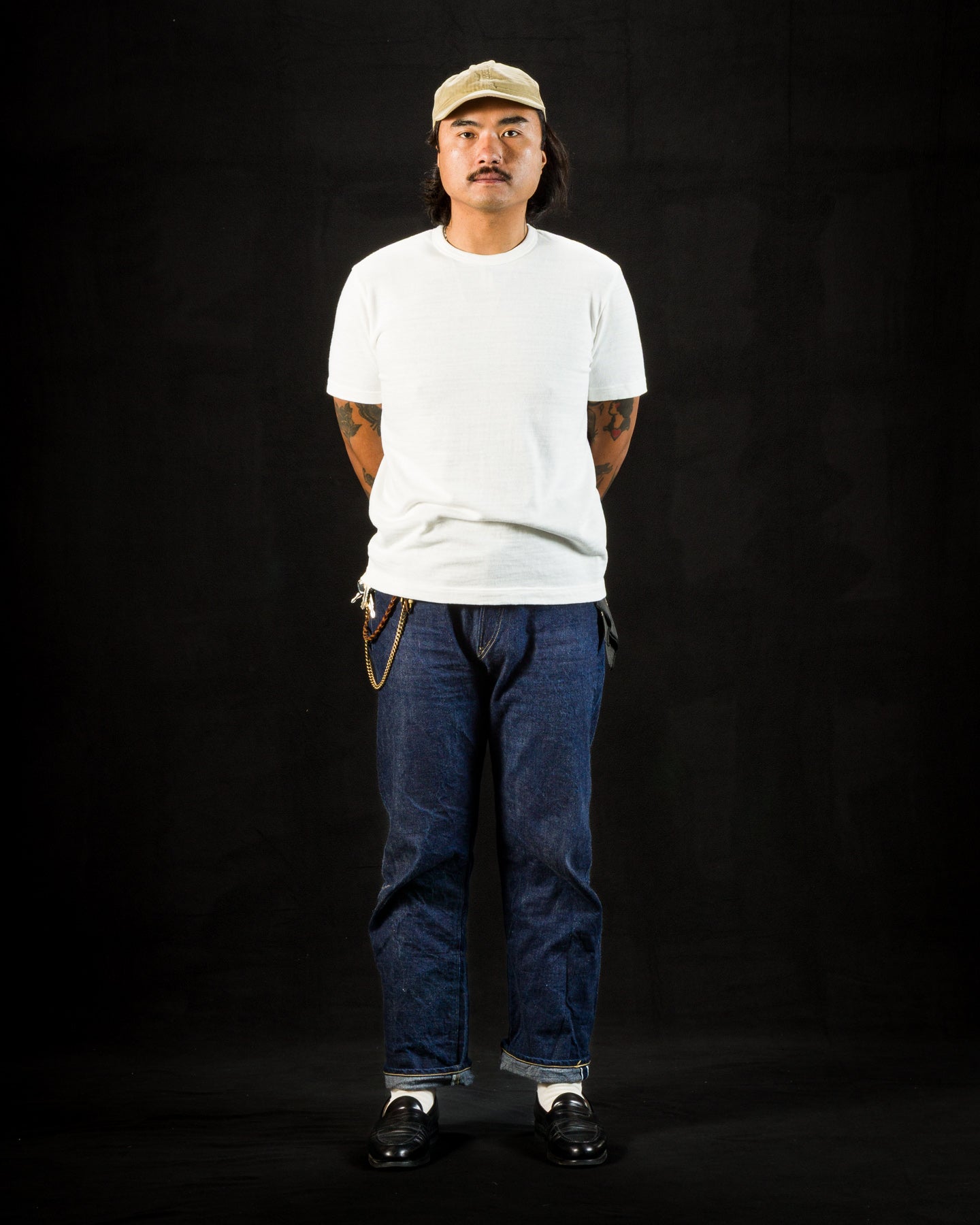

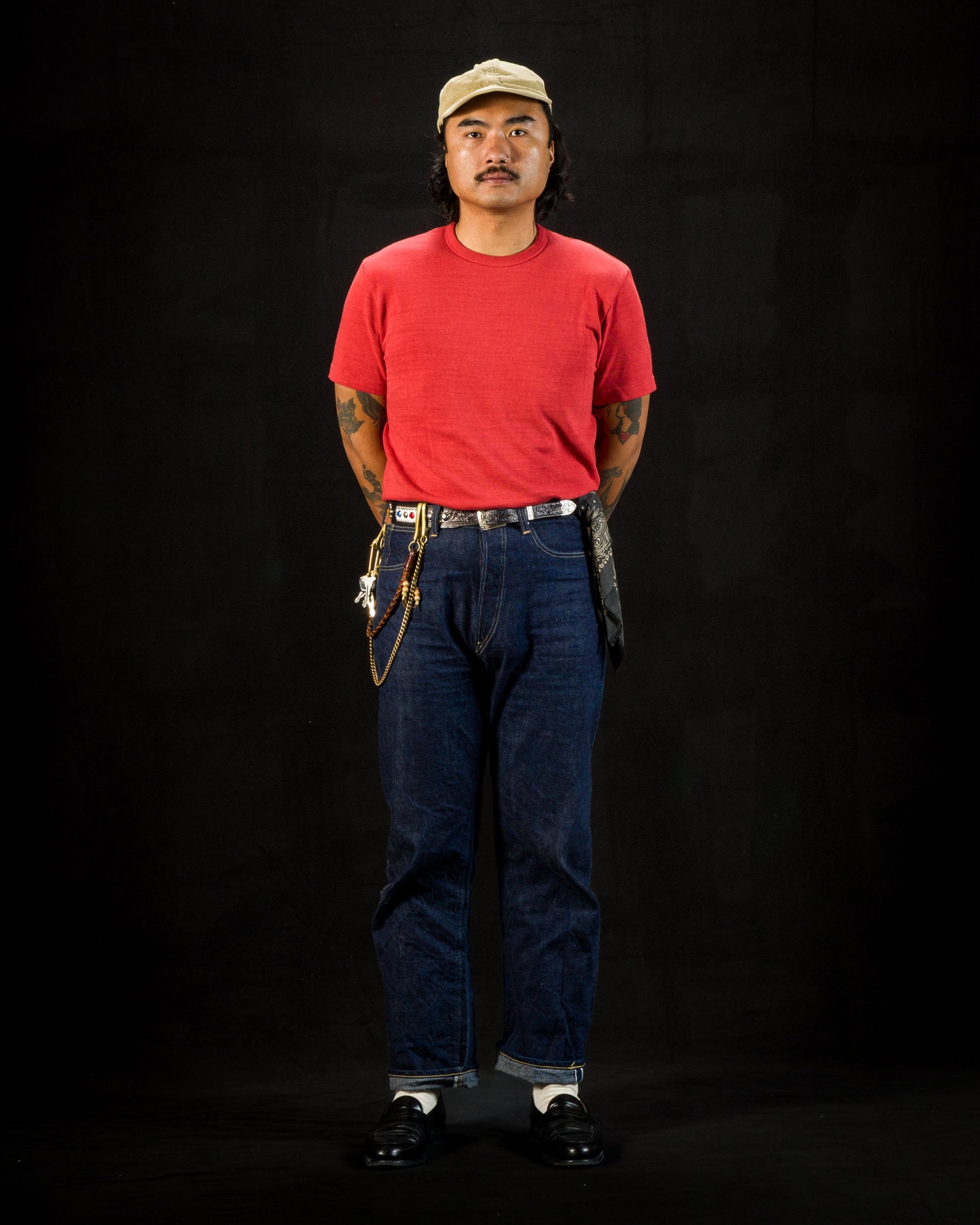

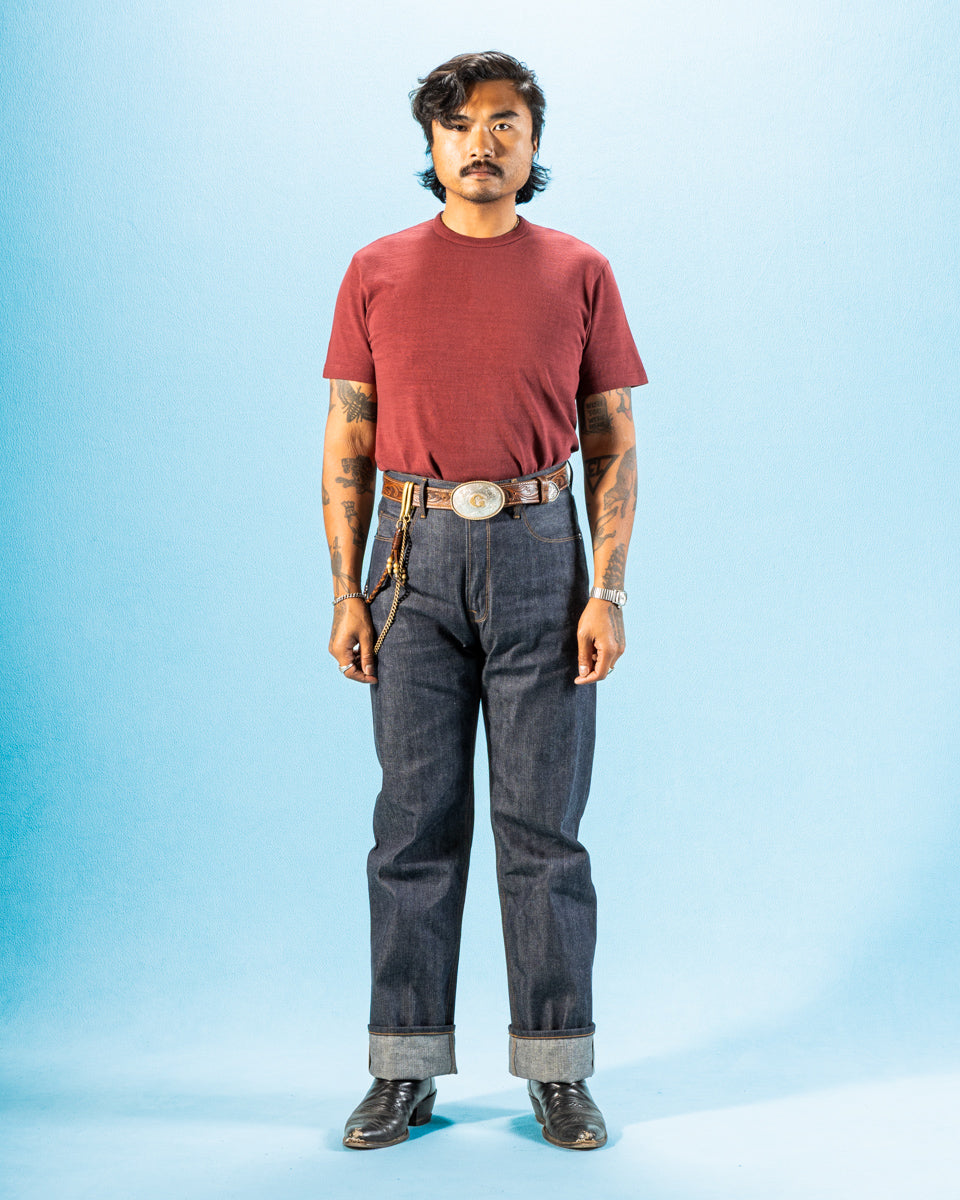

Fit isn’t simple when it comes to tees, especially when working with a textile made on vintage machines. We opted for a slightly more modern, open fit for these tees. Cut a little longer and a little wider than the other loopwheeled tees we carry, these are a fantastic length to wear either tucked or untucked, with a relaxed fit through the chest and comfortably wide shoulders.

Loopwheel tees can be tricky, with unexpected shrinkage or bodies that twist over time due to the lack of side seams. We used super long staple cotton, and pre-shrunk the shirts to eliminate those issues without removing any of the character that makes loopwheel jersey so charming. The combination of the gravity-fed, low-tension fabric and the super long staple cotton create a shirt that is soft and airy without being delicate.

Our new crewneck sweater was also designed to honor vintage styles while enhancing the product. We opted for a cut-and-sew approach rather than using a tubular body for this garment, which is part of our strategy to give each piece as much life as possible. Tubular bodies will twist and shrink over time much more than sewn panels, with little benefit other than aesthetic. The flatlock side seams adds stability to the garment without taking away comfort. The flatseamer sewing process gives a soft, stretchy, comfortable seam with very little bulk but requires quite a bit of skill on the part of the machinist, especially when sewing the complicated lines of our modified raglan sleeve.

The body is once again cut a bit longer to account for the slight shrink over time that all cotton knits experience, and we opted to keep the loopback terry rather than running the fabric through the fleecing process, again with an eye on longevity of wear.

Craft And Industrial Production Meet.

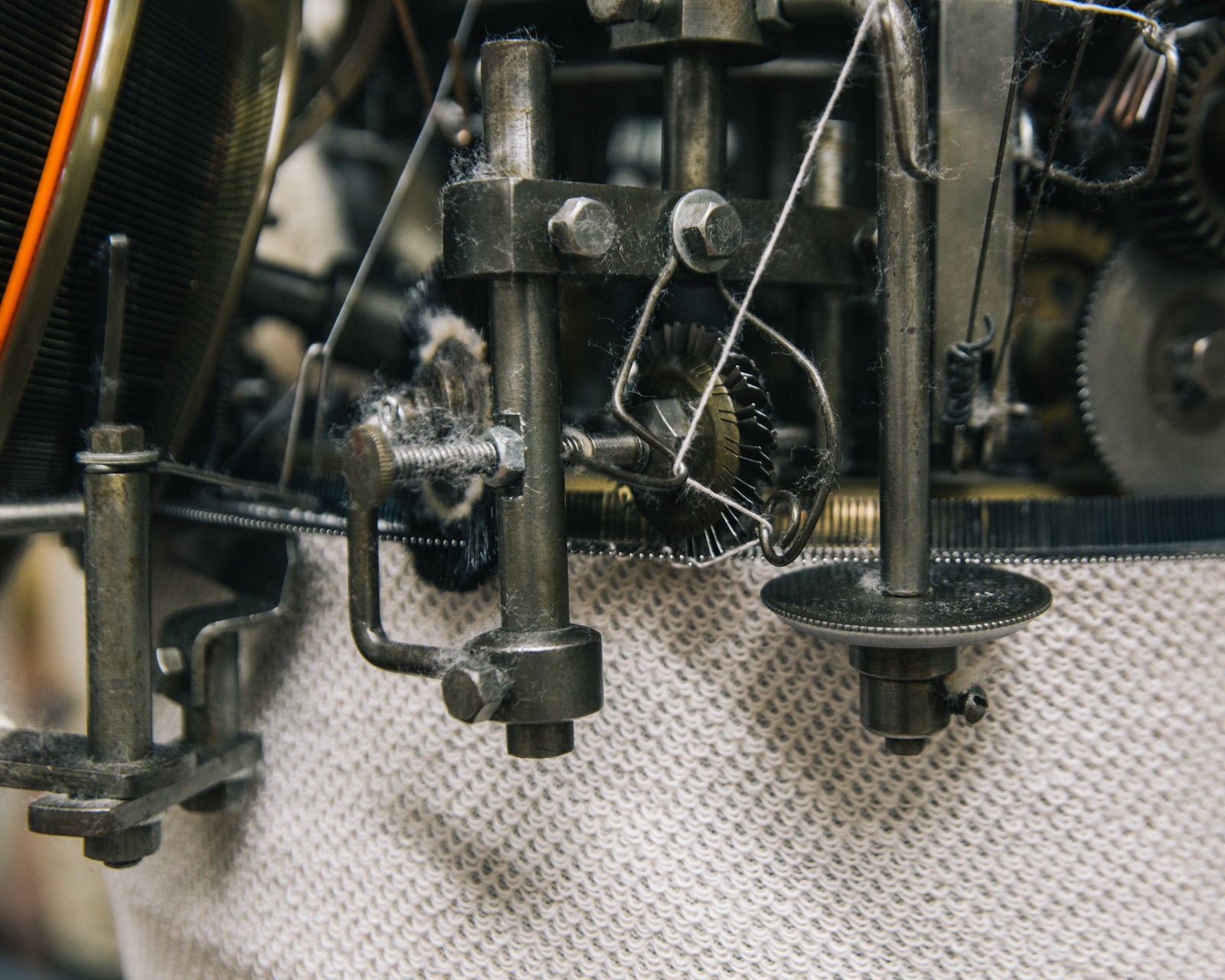

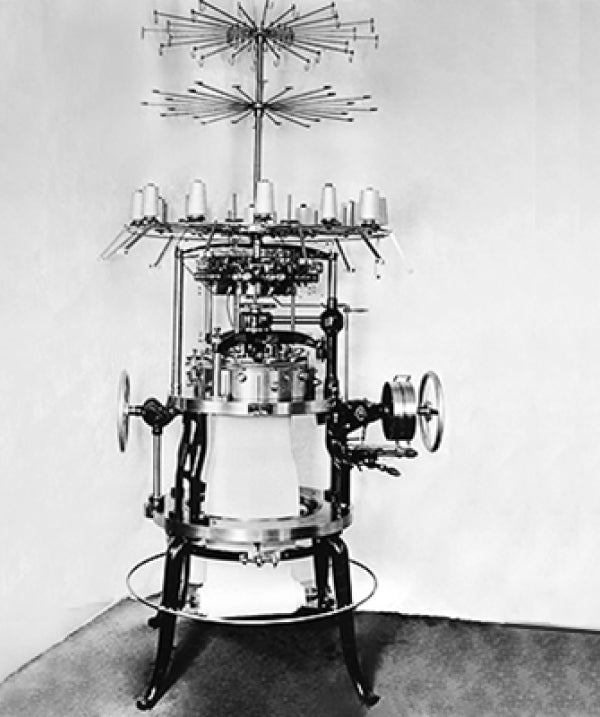

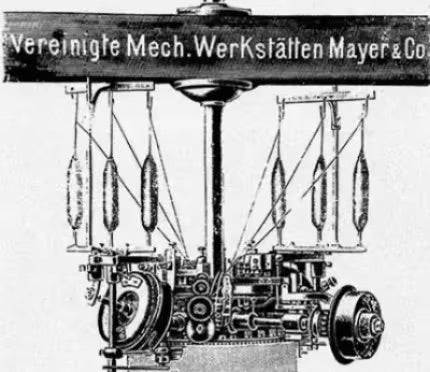

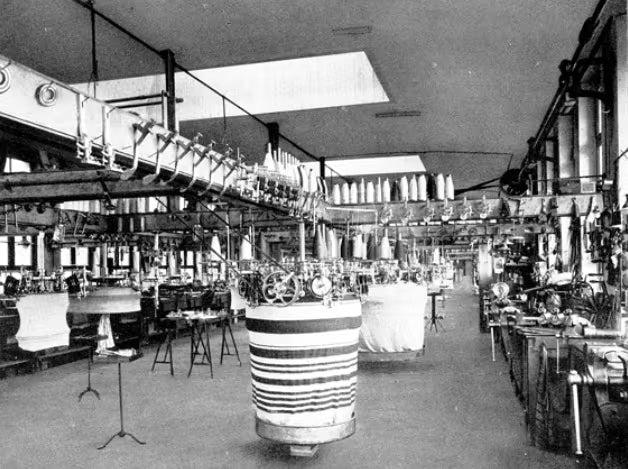

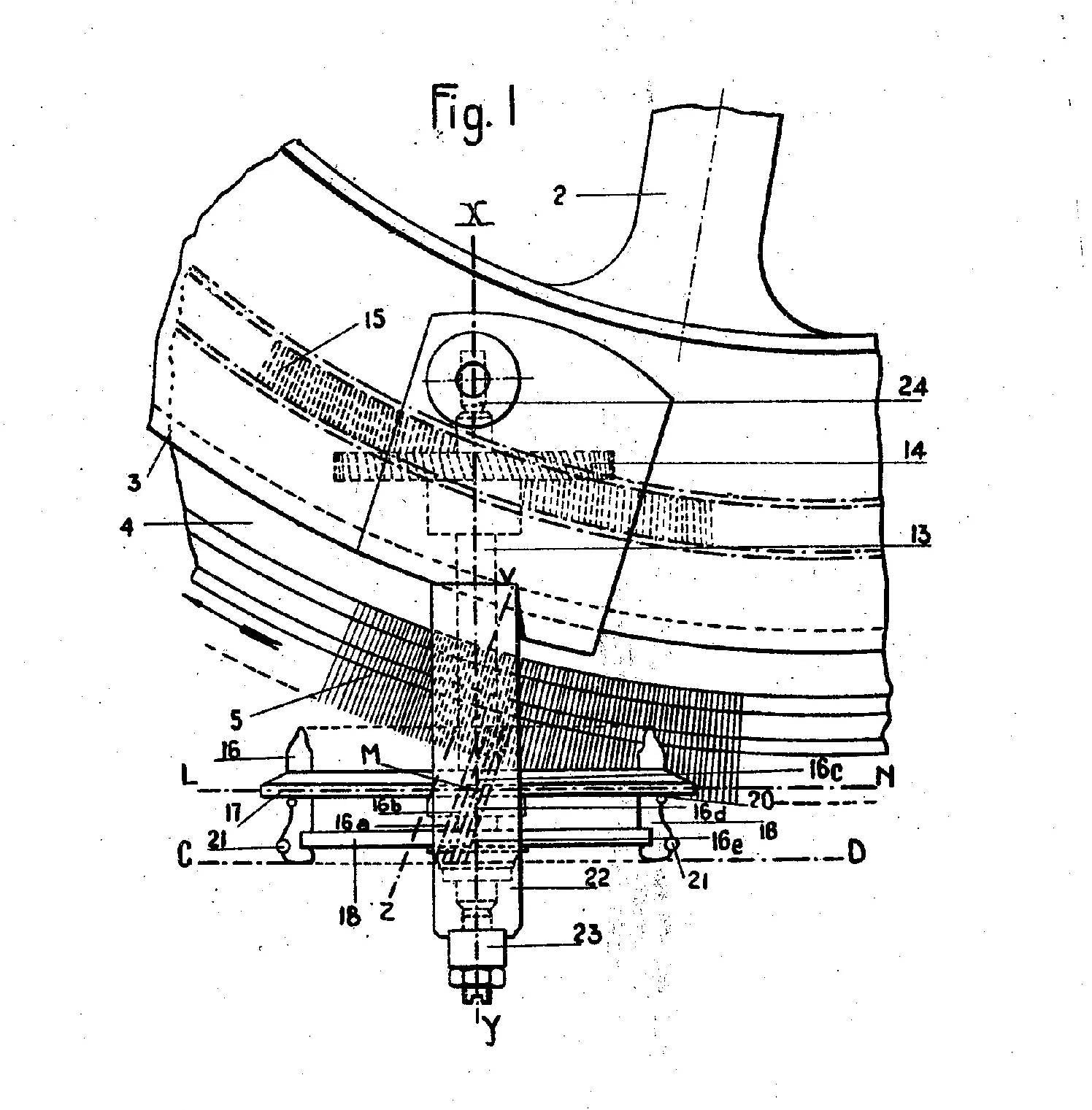

Loopwheel machines hold a particular appeal in opposition to contemporary industrial design. There is nothing sleek or obfuscated about them. Their inner working are open and exposed. The yarn inputs span entire factory floors, and the machines are belt-driven from a central power source rather than having individual motors.

Modern machines are automated and require very little attention to operate. Loopwheelers are far from modern, having been designed in the early 19th century. Getting consistent, high-quality output from one of these delicate beasts is more akin to playing a musical instrument than it is to running a lathe.

Conceptually, loopwheelers sit at the intersection of craft and technology, retaining some of the hand of the maker through the character of the knit. Every meter of fabric knit contains the intent of the manufacturer of the machine and the techinical abilities of the highly skill workers that tend the machine.

Loopwheel In Japan (TSURI-AMI).

Our Wakayama Special Loopwheel Tees are made from fabric knit in Wakayama, Japan, the home of the two remaining Japanese knitting mills using loopwheelers. There were approximately 10 loopwheel mills operating as late as 1995, but price pressure from cheaper imported goods, combined with more efficient (and less expensive) domestic options led to all but the remaining two mills closing.

The first loopwheel machines were imported into Japan in 1909, in support of the Meiji government’s focus on industrialization of the country. Wakayama had a significant base of supporting industries that were complementary to machine knitting with skills in yarn twisting, dying, and machinery; it therefore made sense to build on that base in the transition to mechanized knitting.

Wakayama continued to thrive as a center of textile manufacturing throughout the 20th century. Through good geographic fortune, they avoided the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923 that nearly wiped out Tokyo's knitting industry. Wakayama was not targeted during World War II, preserving the loopwheel machines still in use today.

The machines being brought in were almost certainly made in Germany, in one of the regions that specialized in production of loopwheel circular knitting machines.

Most websites now will cite the machines as being Swiss-made, but a careful inspection of import records and trade histories contradicts this. There is no evidence that any machines of this type were being made in Switzerland, but the Swiss were very active in running trading companies in Japan at the turn of the century.

Comparing archival photographs and drawings from German companies with the machines in place in Japan also supports the conclusion that they are the same machines.

Loose Ends & Fact-checking.

Nearly every article on the web mentions US patent number US1593463A, attributed to Giuseppe Nigra in 1926; these articles also claim that the loopwheeler was invented at that time. We know that the earliest loopwheel machines appeared over 30 years before his patent, and were brought into Japan 17 years before this date. It is unclear what role Nigra played in the circular knitting industry but we will update this article as we learn more.

The other fact frequently presented is that Champion and LL Bean both made loopwheel garments up until 1965. An interview with Satoshi Suzuki, founder of the Japanese brand Loopwheeler, confirms that Champion used loopwheel machines up until 1970 after gradually replacing them with high-speed circular knitting machines starting in 1965. Trade records from the time loosely support this; however, we are still working to get more accurate information about this time.

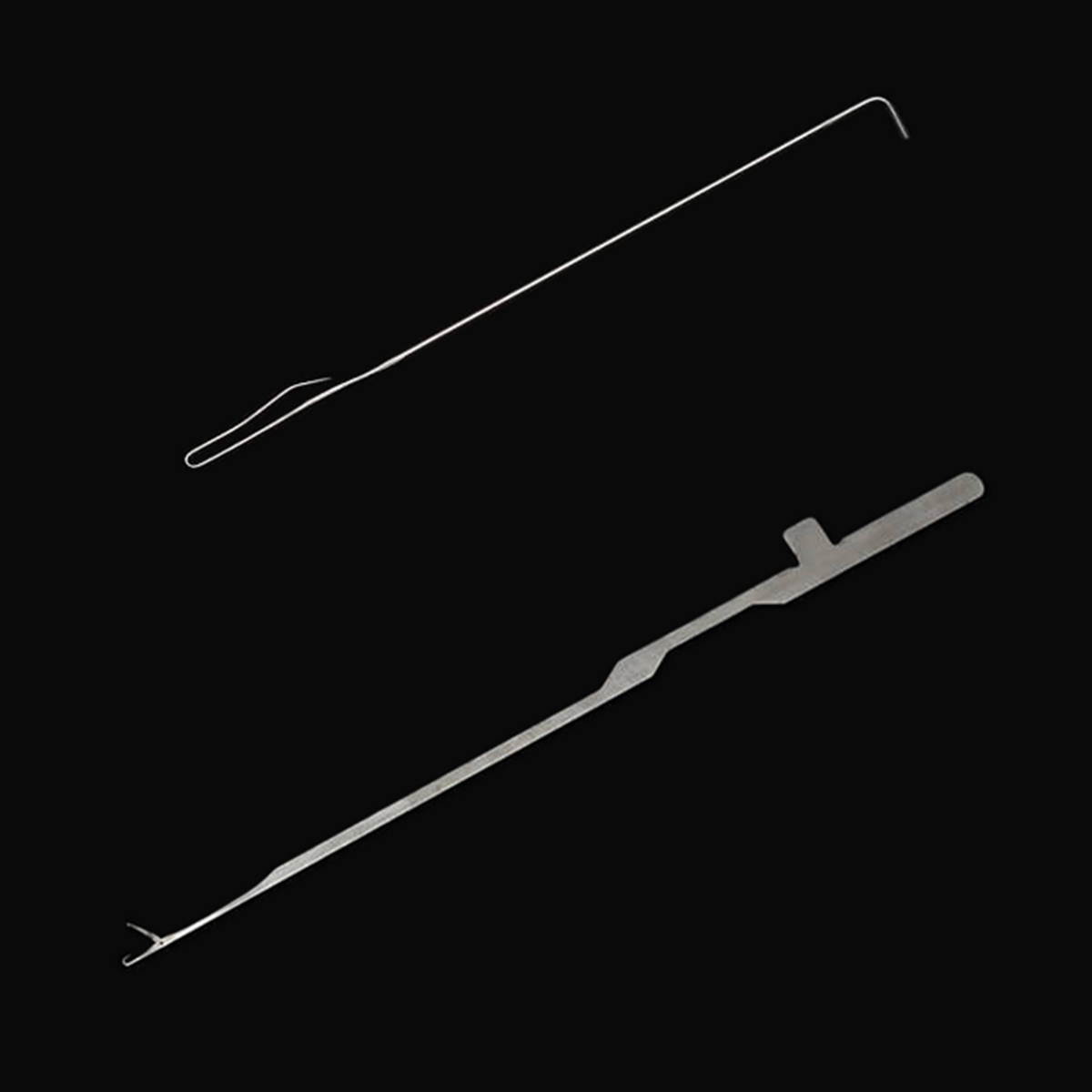

Mentioned earlier, the American Tompkins Upright Rotary Knitting Machine throws a wrench in the mix when it comes to using vintage garments inspection to identify the machines used in production. While the Tompkins was not gravity fed, it was a low-speed machine using bearded spring needles, and produced very similar fabric to a loopwheeler. This makes it a bit harder to verify what company used which knitting technology in a given era.

A Visit to the Source.

In case we haven't made it clear yet, we love loopwheel knits here at Standard & Strange. Although there is seemingly more information than ever floating around the Internet about loopwheel machines and fabrics, much of it is duplicative and derivative. It seemed like the best way to understand these slow-turning beasts and their output would be to just go to the source itself.

The few remaining loopwheel machines in the world live in Japan and Germany. The Japanese ones happen to be where we visit each trip to Japan, in Wakayama, not far from Kobe. With the assistance of our friends at The Real McCoy’s, we were able to set up a visit to one of the mills at the tail end of our fall 2019 trip. Read more...